against the Cross, 6

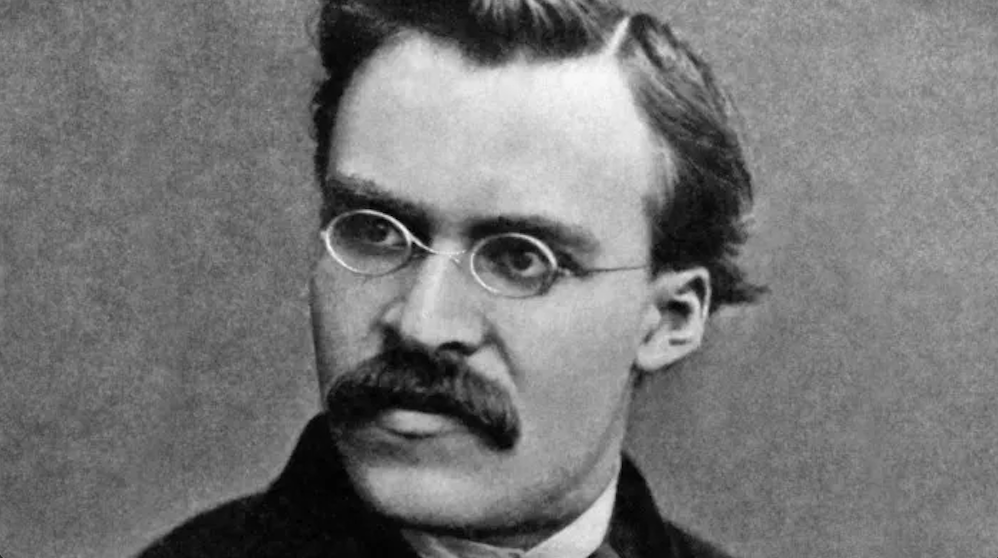

Friedrich Nietzsche in 1867.

Before saying a thing or two about the social impact on the educated sectors of Germany of Nietzsche’s first book, I would like to collect in this and the next entry some revealing anecdotes from the years outlined in the previous entry.

Given that the Nietzsche who would become popular was the philosopher—the hermit Nietzsche, taciturn, myopic and sullen—it is difficult to imagine him cheerful in 1867 when he enjoyed, as he put it, a ‘strong march on foot’ with his faithful friend Rhode: a march in the woods and mountains of Bohemia and Bavaria. Nietzsche had procured sturdy double-soled boots and the experience, which freed him at least for a few days from his academic duties, had Munich and Salzburg as their destination, although they made their way as far as Nuremberg, mostly on foot.

It is also difficult to imagine the philologist gunner whistling Offenbach tunes in the morning, or that the chronic ailments I spoke of vanished that happy season, despite the horse accident as mentioned earlier. The medical examination deduced that he had torn his pectoral muscles, and during therapy, several cups were filled with pus; the sternum was affected and Nietzsche confesses that he had to learn to walk again. Nietzsche’s volume of notes during his convalescence covers many pages, where the philosophical concerns that were to take possession of his soul are absent.

As a professor of classical philology, Nietzsche now earned a decent salary at the University of Basel. For someone born in a humble village, this was like winning the lottery. His mother wrote to him euphorically:

My dear Fritz:

Professor of 800 thalers’ salary! It was too much, my good son and I could not calm my heart in any other way than by immediately sending a telegram to Volkmann in Pforta.

Then I wrote to the good mother, the guardian, the Sidonchen, the Ehrenbergs, Miss von Grimmenstein and the Schenks in Weimar. In the meantime, Mrs Wenkel and Mrs Pinder came to congratulate us, at about 6 p.m. I took my letters to the post office, 25 pages in all, and communicated my joy first of all to the Luthers, who burst into shouts of joy; they called the old privy councillor, and all burst into tears, and heartily congratulated you, as well as Mrs. Haarseim, Mrs. Keil, Mrs. Grohmann with her daughter, Mrs. privy councillor Lepsius, who always shouted: My good son Fritz, as well as Mrs. Von Busch.

And what a beautiful city, said the Keils, the Pinders and old Luther: the university at the top and the Rhine below.

The dream of Nietzsche’s father, who saw it as a prodigy that his firstborn would be born when the king’s birthday bells were ringing, seemed fulfilled. His academic success reinforced the fantasy that Nietzsche would be a genius and probably contributed to that familiar wine going to his head over the years.

And what did his mentor Ritschl have to say? He wrote a eulogy in his reply letter to Wilhelm Vischer, who was envious of the uncouth, medium-sized, light-brown-haired colleague who did not yet dress elegantly. Ritschl wrote:

The man doesn’t even have a doctorate, but only because the obligatory five-year period since completing the baccalaureate (incidentally, taken at Schulpforta) has not yet fully elapsed. Otherwise, he would already have had one. I want to formulate my judgement in a few words, and neither you nor Büchler, Ribbeck, Bernays, Usener [all disciples of Ritschl] or tutti quanti should take it badly.

With as many young people as, for more than thirty-nine years, I have seen being trained before my eyes I have never met, nor have I tried to promote in my speciality according to my possibilities, a lad who so early and so young was as mature as this Nietzsche. The papers for the Rheinisches Museum he wrote in the second and third year of his academic three-year term! He is the first one I have accepted in collaboration while still a student. God willing, he will live a long life. I prophesy that one day he will be at the forefront of German philology.

He is only twenty-four years old; he is strong, vigorous, healthy, bizarre in body and character, made to please similar temperaments. Moreover, he possesses an enviable facility for calm as well as skilful and clear exposition in free expression. He is the idol and unwitting guide of the whole world of young philologists here in Leipzig, quite numerous, who cannot wait to hear him as a teacher.

You will say that I am describing a kind of phenomenon. Well, he is, and a kind and modest one at that. Also, a talented musician, which is irrelevant here. But I have not yet met any active authority who in a similar case has dared to go beyond the formal inadequacy, and I offer my entire philological and scholarly reputation as a guarantee that the thing will have a happy outcome.

No matter how much of a nose for academic talent Professor Ritschl might boast, he never imagined that his protégée was a time bomb that would blow apart the cloistering he had been suffering from since childhood. Instead of the grey monotony of Pforta that continued in Bonn, Leipzig and now Basel, Nietzsche would end his last sane days singing to the God Dionysus. The very intense blue sky seen in the islands of ancient Hellas, to which Nietzsche always aspired, evokes another flight from the gloomy skies of the north to the limpid south.

Vincent van Gogh, who lived within Nietzsche’s lifespan, was also the son of an austere and humble, though Dutch, Protestant pastor.

Unlike Nietzsche, Vincent would become a Protestant pastor for a time, at the age of twenty-six, and go as a missionary to a mining region of Belgium in search of the crucified of the time: a sort of St. Francis in a Protestant version. Only after prolonged self-mortifications would Brother Vincent abandon this black period of his life—literally black, as he watched the poor miners leaving the mines covered in charcoal—and flee in search of the enlightened landscapes of Arles (Nietzsche would do something similar, but not in the South of France but in Italy).