‘The action of the victors shut out all hope for the future. Outlawed, without any rights, Germany was a colony of the Allies; the British especially treated Germans as they did formerly with the natives of their colonies’ said Rolf Koseik, in Deutschland in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 1995. Erich Hentschel, publisher of the highly recommended special edition of Heimatbrief Saazerland (letter to my Saazerland Homeland), in commenting on the thoughts in connection with the 8 May 1945, quite rightly states that this historic date and its consequences are experienced within Germany in several, quite different, ways:

In the first place there were the inmates of prisons and concentration camps, then there were prisoners of war and forced labourers, also volunteer foreign workers and, indeed, true believer fighters in resistance too, all of whom would have welcomed the end of the Third Reich as liberation, rightly so from their point of view. For the great mass of the German population, however, the end of the war is associated with humiliation, deprivation of rights and hopelessness. It meant the loss of identity and all traditional values, persecution, rape, imprisonment, torture and often also death.

The citizens in the German Eastern provinces especially had to suffer terrible persecutions. For twelve and a half million East Germans the end of the war meant flight and expulsion, confinement in refugee camps, maltreatment and rape amidst orgies of indescribable violence and murder… When, during commemorations of the war’s end, the people in the Federal Republic are persuaded by the politicians, media, bishops and various other ‘personalities’ that they should consider themselves, if you please, as having been ‘liberated’, this is sheer cynicism and utter contempt, if not to say ignorance and stupidity.

There were also a few rays of hope during the ‘liberation’. Not all members of other nations were opportunistic or showed fundamental hostility towards the Germans. Concerning the relationship between the foreign civilian population and the native German population, it must be emphasised, first and foremost, that in an almost chivalrous fashion the people of Latvia and Lithuania above all others assisted the suffering Germans, as much as they possibly could.

The Latvians’ and Lithuanians’ selfless hospitality and willingness to help are documented in many of the essays based on personal experience. Käthe Dell, who was fifteen years old at the time, still remembers with gratitude: ‘The Lithuanians always helped us, even if it meant sharing their last crust of bread’.

Martha Kurzmann, a seamstress who was driven from her home in Konigsberg, agrees wholeheartedly: ‘That country with its selfless hospitality, innate generosity and love of everything German saved the lives of countless thousands of East Prussians’, and Frau L. Freiheit takes the same line. Facing starvation, she made her way with her only surviving child to Lithuania, ‘where we were accepted everywhere with great humanity and love’.

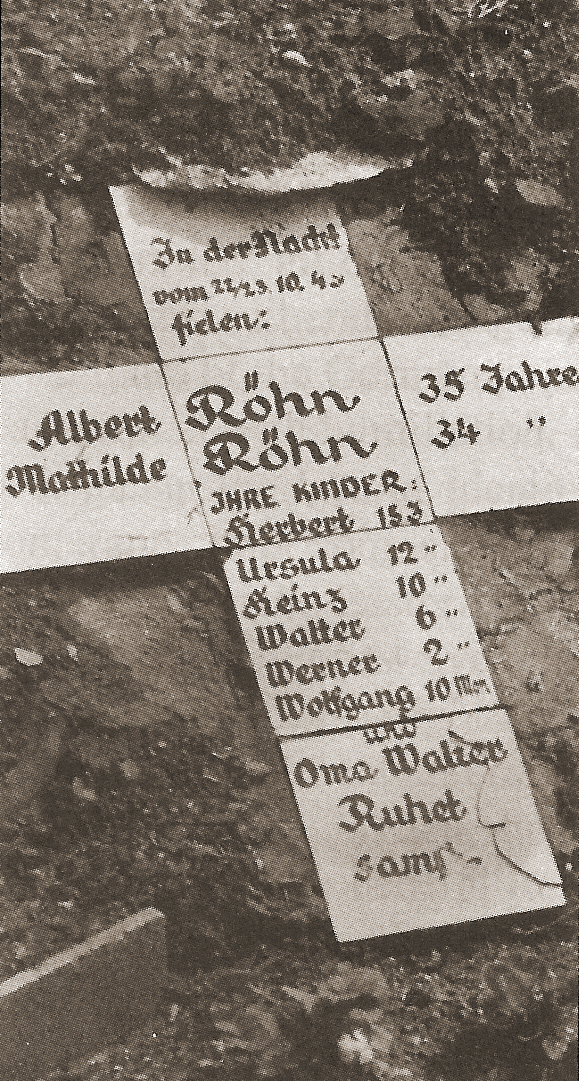

(Left, a German family annihilated in the Allied bombing raid of Kassel, October, 1943.) Furthermore, the Lithuanians aided the starving Germans at great risk and danger to themselves: ‘The Lithuanians and Latvians helped us whenever they could. Even though it was forbidden to help us, even though the Russians threatened them with heavy fines and deportation to Siberia if they gave us food or shelter, they assisted us anyway.’

(Left, a German family annihilated in the Allied bombing raid of Kassel, October, 1943.) Furthermore, the Lithuanians aided the starving Germans at great risk and danger to themselves: ‘The Lithuanians and Latvians helped us whenever they could. Even though it was forbidden to help us, even though the Russians threatened them with heavy fines and deportation to Siberia if they gave us food or shelter, they assisted us anyway.’

In remembrance of the countless Europeans fighting alongside Germany during the war, it must be mentioned that in almost all the European countries severe persecution was taking place, following their ‘liberation’ by Allied troops. After the ceasefire hundreds of thousands of people were hounded down, tortured, hauled before tribunals on charges of ‘collaboration’ and ‘treason’, often condemned to death, while huge numbers of women and men were murdered in the streets by mobs. Bloody retribution was meted out by self-appointed judges, jailers and executioners in Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Norway and France.

One of the most tragic events in this connection has to be the British handing over of the Cossacks and their families to the Soviets at Lienz on 1 June 1945, as well as Sweden’s handing over of German and Baltic soldiers to the Soviets in December 1945. Illegal under international law, these decisions were tantamount to a gruesome death sentence—dreadful scenes were taking place there.