Further to my previous post. Below, (1) my presentation of Colin Ross’ cornerstone to understand the trauma model of mental disorders; (2) a translation of “Regaining Self-esteem” by Dr. Claus Wolfschlag—original in German here—, and (3) my views on traumatized Germany.

1.- Ross’ trauma model

Note of August 25, 2017: Today I will move this text to an entry quoting my book Day of Wrath, where the text properly belongs.

2.- Wolfschlag’s translated piece

A note was sent to me about the topic of “Trauma, fear and love.” The psychotherapist Franz Ruppert from Munich has dealt with so called “trauma energies” in his books, a trauma that can be passed down through generations. Because individual psychological findings can at least partially be transferred to collective experiences, I have read the slides on “perpetrators” and “victims” from Ruppert’s website from this vantage point.

A fortnight ago I wrote an article about some recent movies where the subject of the expulsion of civilian Germans after 1945 plays an important role. But such artistic products of processing the trauma are still rare and on individual cases. There is a striking imbalance in the German “culture of remembrance.” Since the 1970s the Holocaust and the persecution of leftist-resistance groups during the Nazi period have obtained a dominant, partly sacralized meaning while German victim stories of those years, which could also incriminate other actors as “perpetrators,” have increasingly been hidden and marginalized.

If occasionally an audible voice rises intending to give these German victims their right in the German “culture of remembrance,” it will immediately be attacked with the rationale of equating “victims and perpetrators” and that the dead Germans are, at most, victims of second or third class. This lesson was learned and requires constant repetition, since it is ultimately a very important tool to preserve the foreign political control over the economically important German industrial base.

Passivity is an emergency response of the victim

In conservative circles it is frequently heard that since 1945 Germany would be in a traumatized phase. In this context the words of Ernst Jünger have been recorded: “From such a loss one cannot recover.”

So now I had this in mind when I looked at the slides of Franz Ruppert, which appeared to me like an incidental proof of the theory of “the traumatized nation.” After Ruppert’s definition of the terms “perpetrator” and “victim,” he goes on to explain that the victim would make the damage even bigger with a stress reaction to the suffering inflicted upon him or her. A failure to react is, therefore, an emergency response of the victim to maximize her chances of survival. The victim gives in to the situation, but experiences herself as helpless and powerless.

Presently this reaction can be seen very clearly in the behavior of the Germans after the end of the War; it partly persists even to these days. One must give up on further acts of resistance and surrender oneself into a feeling of political powerlessness. This in spite of the fact that for some political groups there are now separate possibilities of participation and new beginnings. I speak of the collective, national, fundamental experience. According to Ruppert, the splitting of the personality allows the traumatized individual to live on. It is a survival strategy, and it means the victim’s experience will be suppressed and split off. The traumatization will be denied; memories will be tried to be erased, and impulses of resistance suppressed.

The prosperous Germany is only very moderately happy

The result of this repression, according to Ruppert, are feelings of guilt. In addition to it, it comes the imagination that the wounds, which one has suffered personally, are “fair punishment.” One doesn’t perceive the perpetrator as such, but rather defends him. The individual even identifies herself with the needs of the perpetrator.

As a side effect the traumatization shows itself in constant complaining, suffering, bemoaning without being able to give cogent reasons for it. According to an assessment [linked at the original article], the affluent Germany only takes a middle place on a map of Europe ranked by perceived happiness. And that alongside poorer eastern European countries, which have to process their own traumatizations due to Soviet occupation. The people of the poorer western European nations on the other hand are interestingly almost happier than the Germans. Why?

For the perpetrator the traumatization also has consequences. He denies the injury inflicted on other humans, even feels justified. He blames and ridicules the victim and declares to have acted on behalf of a higher thought. This behavior is often the result of an earlier victimhood of the perpetrator and a misguided coping strategy. It leads to events such as the recent election in the Czech Republic, where Miloš Zeman could win the presidential elections with his defensive nationalistic position against Karel Schwarzenberg, who cautiously reminded us the historic suffering of the Sudeten-Germans.

Learning to mourn, developing compassion for oneself

Franz Ruppert comes to the conclusion that unprocessed experiences of victimization can turn into eruptive perpetrator behavior. The powerlessness can be followed by a furious outbreak of aggression. Victims turn into perpetrators, and the lack of emotion towards oneself leads to a lack of empathy towards the new victim. In this way victim-perpetrator spirals keep running: a power which can be seen interpersonally and also in the larger political conflicts. Innocent people are dragged into the conflicts, and it comes to delusions and acts of self-destruction.

An eruption of violence is not yet to be expected from the Germans in their current state. Perhaps nothing will ever come from them again, except a last gasp on the deathbed. But maybe one can at least try to heal a couple of things.

Healing would, however, require a massive reform of our “culture of remembrance.” This would, let’s not delude ourselves, encounter the most brutal resistance since this is where the core of the trauma is located [emphasis added], in which influential people have a vested interest.

For the healing process one can therefore transfer the problem-solving approach from the individual of Ruppert to the national situation. First of all one has to acknowledge one’s own traumatization and psychological injuries, but also learn to mourn for oneself, to develop compassion for oneself. Finally, although one must refrain from blind vengeance it is by all means appropriate to “demand from the perpetrator a concrete compensation for the damage, if still possible” (Ruppert).

Only compensation can bring healing

One can speak of compensation, and if it only consists of the annulment of the discriminatory Benesch-decrees in the Czech Republic, the construction of memorial sites for the displaced Germans in the Czech Republic and Poland, bilingual place signs and symbolic material compensations, a memorial for the German victims of the bombing campaign must also be constructed in London and Washington; in Moscow, another for the German Gulag-slaves and the women who were raped by the Red Army.

Only then will the false and traumatized relations of today be overcome. Only then will constructive symbiotic relations be possible, from which all participants can profit.

At the end of this process stands for all sides the rediscovery of self-respect. Because for the perpetrator too the acknowledgement of responsibility for his own deeds is a way to inner healing.

The problem of the German process of coming to terms with the past is, after all, not the examination of one’s own crimes but rather the one-sidedness, the political instrumentalization and anti-German manipulation. The healing process, which was outlined here, has for now been delayed in the Czech Republic due to the electoral defeat of Schwarzenberg. However, time and again it will knock against the coffin lid from below, no matter how much earth one hurls onto it.

3.- My 2 ¢

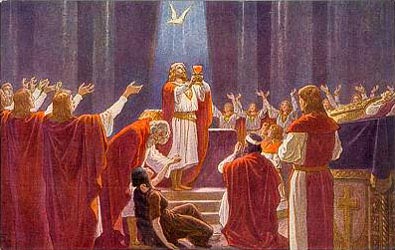

Today’s Germans, so attached to the Judeo-American perp and overburdened with guilt, remind me the character of the badly wounded Amfortas in Wagner’s last opera, Parsifal.

(See YouTube clip of track 7 of Parsifal’s Act I: here)

Unlike Wolfschlag, I believe that only full revenge heals the wounded soul, even if it comes from Above, not from Below. The good news for German nationalists is that they will soon be gloating after the dollar crashes and Murka burns. Together with an England overwhelmed by immigrants, as depicted in the film Children of Men, the fall of the US will do the healing trick with no need of Teutonic violence—insofar as the subversive tribe that my beloved Nazis wanted to deport from Europe is directly involved in their ongoing / coming fall.

I call this poetic justice (Murkans really lost the War because they fought on the side of those who would one day enslave them)…

The Russians on the other hand have already suffered a lot after their incredible blunder: allowing the empowerment of Jewry right after the Bolshevik Revolution, where dozens of millions of Slavs were killed. But yes: the Russians must erect monuments commemorating the German victims anyway.

Only thus can Amfortas fully heal.