Editor’s note: This Monday I begin quoting excerpts from The Jesus Hoax by American professor David Skrbina. As his book is six chapters long, unless something unforeseen comes up I will finish quoting these excerpts from his book on Saturday.

______ 卐 ______

CHAPTER 1: SETTING THE STAGE

There are about 2.1 billion Christians on Earth today, roughly 1/3 of the planet, making Christianity the #1 religion globally. The United States is strongly Christian; about 77% of Americans call themselves Christians.

But some historians and researchers have made a startling claim: that Jesus, the Son of God, never existed. They say that Jesus Christ was a pure myth. Is that even possible? Surely not, we reply. This most-influential founder of the most-influential religion of Christianity surely had to exist. And he surely had to be the miracle-working Son of God that is proclaimed in the Bible. How could it be otherwise? we ask. How could a venerable, two thousand-year-old religion, with billions of followers throughout history, be based on someone who never existed? Impossible! Or so we say.

If that were the case, if Jesus never existed, imagine the consequences: an entire religion, and the active beliefs of billions of people, all in vain. All of Christianity based on a myth, a fable, even—as I will argue—a lie. Why, that would be catastrophic…

Note that it’s very important to distinguish between the two conceptions of ‘Jesus.’ If someone asks, “Did Jesus exist?” we need to know if they mean (a) the divine, miracle-working, resurrected Son of God (sometimes called the biblical Jesus), or (b) the ordinary man and Jewish preacher who died a mortal death (sometimes called the historical Jesus). Christianity requires a biblical Jesus, but the skeptics argue either for simply an historical Jesus—which would mean the end of Christianity—or worse, no Jesus at all.

I will, however, accept the historical Jesus…

Another Jesus Skeptic?

So, why this book? Why do we need yet another Jesus skeptic?

To answer this question, let me give a brief overview of some of the prominent skeptics and their views. I will argue that their ideas, though on the right track, are woefully short of the truth. They lack the courage or the will to look hard at the evidence, and to envision a more likely conclusion: that Jesus was a deliberately constructed myth, by a specific group of people, with a specific end in mind. None of the Christ mythicists or atheist writers have, to my knowledge, articulated the view that I defend here.

But first a quick recap of the background and context for the idea of a mythological Jesus. The earliest modern critic was German scholar Hermann Reimarus, who published a multi-part work, Fragments, in the late 1770s. Strikingly, his view is one of the closest to my own thesis of any skeptic. For Reimarus, Jesus was the militant leader of a group of Jewish rebels who were fighting against oppressive Roman rule. Eventually he got himself crucified. His followers then constructed a miraculous religion-story around Jesus, in order to carry on his cause. They lied about his miracles, and they stole his body from the grave so that they could claim a bodily resurrection. This is quite close to what I will call the ‘Antagonism thesis’—that a group of Jews constructed a false Jesus story, based on a real man, in order to undermine Roman rule. But there is much more to the story, far beyond that which Reimarus himself was able to articulate.

In the 1820s and 30s, Ferdinand Baur published a number of works that emphasized the conflict between the early Jewish-Christians—significantly, all the early Christians were Jews—and the somewhat later Gentile-Christians. This again is a key part of the story, but we need to know the details; we need to know why the conflict arose, and what were its ends.

In 1835, David Strauss published the two-volume work Das Leben Jesu—“The Life of Jesus.” He was the first to argue, correctly, that none of the gospel writers knew Jesus personally. He disavowed all claims of miracles, and argued that the Gospel of John was, in essence, an outright lie with no basis in reality.

German philosopher Bruno Bauer wrote a number of important books, including Criticism of the Gospel History (1841), The Jewish Question (1843), Criticism of the Gospels (1851), Criticism of the Pauline Epistles (1852), and Christ and the Caesars (1877). Bauer held that there was no historical Jesus and that the entire New Testament was a literary construction, utterly devoid of historical content. Shortly thereafter, James Frazer published The Golden Bough (1890), arguing for a connection between all religion—Christianity included—and ancient mythological concepts.

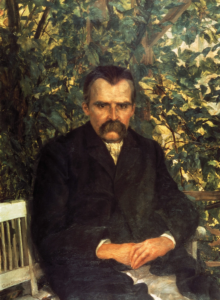

It was about at this time that another famous Christian skeptic emerged: Friedrich Nietzsche. In his books Daybreak (1881), On the Genealogy of Morals (1887), and Antichrist (1888) he provides a potent critique of Christianity and Christian morality. Nietzsche always accepted the historical Jesus, and even had good things to say about him.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: I think I am a better scholar of Nietzsche than Skrbina. In one of his excellent translations of Nietzsche’s books, the Spaniard Andrés Sánchez Pascual quoted a passage in which Nietzsche said that Jesus was an idiot. Seven years ago I quoted Nietzsche’s posthumous fragment here.

Editor’s note: I think I am a better scholar of Nietzsche than Skrbina. In one of his excellent translations of Nietzsche’s books, the Spaniard Andrés Sánchez Pascual quoted a passage in which Nietzsche said that Jesus was an idiot. Seven years ago I quoted Nietzsche’s posthumous fragment here.

I first read that fragment from the isolated manuscripts left by Nietzsche in one of the books published in Spain by Alianza Editorial, but I haven’t heard of English speakers quoting it. I refer to page 132 of El Anticristo, which I read in 1976, where Sánchez Pascual speaks of Nietzsche’s criticism of Renan regarding Jesus’ alleged ‘genius’ and ‘heroism’. Skrbina continues:

______ 卐 ______

But he was devastating in his attack on Paul and the later writers of the New Testament. He viewed Christian morality as a lowly, life-denying form of slave morality, attributed not to Jesus but to the actions of Paul and the other Jewish followers. Along with Reimarus, Nietzsche provides the most inspiration for my own analysis.

Into the 20th century, we find such books as The Christ Myth (1909) and The Denial of the Historicity of Jesus (1926), both by Arthur Drews, and The Enigma of Jesus (1923) by Paul-Louis Chouchoud. All these continued to attack the literal truth claimed of the Bible.

More recently, we have critics such as the historian George Wells and his book Did Jesus Exist? (1975). Here he assembles an impressive amount of evidence against an historical Jesus. Bart Ehrman has called Wells “the best-known mythicist of modern times,” though in later years Wells softened his stance somewhat; he accepted that there may have been an historical Jesus, although we know almost nothing about him. Wells died in 2017 at the age of 90.

Similar arguments were offered by philosopher Michael Martin in his 1991 book, The Case against Christianity. Though a wide-ranging critique, he dedicated one chapter to the idea that Jesus never existed. Martin died in 2015.

Among living critics, we have such men as Thomas Thompson, who wrote The Messiah Myth (2005); he is agnostic about an historical Jesus, but argues against historical truth in the Bible. By contrast, Earl Doherty (The Jesus Puzzle, 1999), Tom Harpur (The Pagan Christ, 2004), and Thomas Brodie (Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus, 2012) all deny that any such Jesus of Nazareth ever existed. Richard Carrier, in his book On the Historicity of Jesus (2014), finds it highly unlikely that any historical Jesus lived.

Perhaps the most vociferous and prolific Jesus skeptic today is Robert Price, a man with two doctorates in theology and a deep knowledge of the Bible. Price’s central points can be summarized as follows:

1) The miracle stories have no independent verification from unbiased contemporaries.

2) The characteristics of Jesus are all drawn from much older mythologies and other pagan sources.

3) The earliest documents, the letters of Paul, point to an esoteric, abstract, ethereal Jesus—a “mythic hero archetype”—not an actual man who died on a cross.

4) The later documents, the Gospels, turned the Jesus-concept into an actual man, a literal Son of God, who died and was risen…

With the exception of Nietzsche, all of the above individuals exhibit a glaring weakness: they are loathe to criticize anyone. No one comes in for condemnation, no one is guilty, no one is to blame for anything. For the earliest writers, I think this is due primarily to an insecurity about their ideas and a general lack of clarity about what likely occurred. For the more recent individuals, it’s probably attributable to an in-bred political correctness, to a weakness of moral backbone, or to sheer self-interest. In recent years, academics in particular are highly reticent to affix blame on individuals, even those long-dead. This is somehow seen as a violation of academic neutrality or professional integrity. But when the facts line up against someone or some group, then we must be honest with ourselves. There are truly guilty parties all throughout history, and when we come upon them, they must be called out…

For now I simply note that none of our brave critics, our Jesus mythicists, seem willing to pinpoint anyone: not Paul, not his Jewish colleagues, not the early Christian fathers —no one. A colossal story has been laid out about the Son of God come to Earth, performing miracles, and being risen from the dead, and yet—no one lied? Really? Can we believe that? Was it all just a big misunderstanding? Honest errors? No thinking person could accept this. Someone, somewhere in the past, constructed a gigantic lie and then passed it around the ancient world as a cosmic truth. The guilty parties need to be exposed. Only then can we truly understand this ancient religion, and begin to move forward.